by

Christopher Barr

“What I hate is ignorance, smallness of imagination,

the eye that sees no farther than its own lashes. All things are

possible. Who you are is limited only by who you think you are.”

– Egyptian Book of

the Dead

“We do not have to visit a madhouse to find disordered minds; our planet is the mental institution of the universe.”

– Goethe

Nostalgia is denial,

denial of the painful present.

Midnight in Paris is an inspiring

film, a film filled with joy and wonder during a time in the canon where

there’s been very little of that.

Gil Pender is a dreamer that fanaticizes about living

in the past, specifically 1920’s Paris. His fiancée, Inez and her

Republican parents are in Paris with him. Everyone around Gil is

superficial and pretentious and he, a pacifist, lets them didactically walk all

over him. Gil wants to explore the fine city of Paris but his fiancée and

her mother want to just blindly shop.

They don’t see the beauty in Paris that Gil sees. Gil’s fiancée and her parents are out of their

element in Paris, they want the comforts of America and they find the culture

in Paris more annoying than anything, because how unAmerican it truly is.

Gil Pender is a dreamer that fanaticizes about living

in the past, specifically 1920’s Paris. His fiancée, Inez and her

Republican parents are in Paris with him. Everyone around Gil is

superficial and pretentious and he, a pacifist, lets them didactically walk all

over him. Gil wants to explore the fine city of Paris but his fiancée and

her mother want to just blindly shop.

They don’t see the beauty in Paris that Gil sees. Gil’s fiancée and her parents are out of their

element in Paris, they want the comforts of America and they find the culture

in Paris more annoying than anything, because how unAmerican it truly is.  Gil is treated like a child for the most part while

with his fiancée, who orders him around and tells him to be quiet when her

pompous friend Paul spews pedantic discernments about Rodin, Monet or his

so-called insights on wine. Gil is alone among the people in his life

that are all drowning in self-interest and ego.

Gil is treated like a child for the most part while

with his fiancée, who orders him around and tells him to be quiet when her

pompous friend Paul spews pedantic discernments about Rodin, Monet or his

so-called insights on wine. Gil is alone among the people in his life

that are all drowning in self-interest and ego.Out walking by himself, inebriated, along the romantic back streets of Paris, Gil is invited into an old car filled with jovial Parisians for drinks and laughter. Gil goes along but after meeting F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald and listening to the live piano playing of Cole Porter at a bar, he begins to realize, to his disbelief, that he is in fact in 1920’s Paris. Understandably Gil is in shock but soon just goes with it and enjoys himself.

At a café he meets Ernest Hemingway, another one of

his idols, and discusses his novel that he is writing. Gil’s been

reluctant to show his novel to anyone in his present, likely because he feels

they won’t get it and thus they won’t get him, and quite frankly, most of them

are idiots. His desire to live in the past stems from him not being taken

seriously in his present. This type of thinking comes from

the fantasy of the mind; we begin to romanticize a sort of success for

ourselves when no one in the real world cares.

At a café he meets Ernest Hemingway, another one of

his idols, and discusses his novel that he is writing. Gil’s been

reluctant to show his novel to anyone in his present, likely because he feels

they won’t get it and thus they won’t get him, and quite frankly, most of them

are idiots. His desire to live in the past stems from him not being taken

seriously in his present. This type of thinking comes from

the fantasy of the mind; we begin to romanticize a sort of success for

ourselves when no one in the real world cares.Gil asks Hemingway to read his novel, leaves the café and is suddenly transported back to the present. While back with his bossy fiancée, Gil thinks about the night before, likely working out the reality of such a fantastical happening.

Back in the 1920’s, Gil meets a girlfriend of Pablo

Picasso named Adriana and instantly and understandably falls for her. After talking to

her he discovers that she wishes she lived in 1890’s Paris. She is a

dreamer of good times long past, just like Gil, and wishes to live in the past

and discard the present as prosaic.

Back in the 1920’s, Gil meets a girlfriend of Pablo

Picasso named Adriana and instantly and understandably falls for her. After talking to

her he discovers that she wishes she lived in 1890’s Paris. She is a

dreamer of good times long past, just like Gil, and wishes to live in the past

and discard the present as prosaic.

As the reality of his fantasy of living in 1920’s

Paris expands, Gil runs into surrealist painter Salvador Dali and has a

wonderful talk about love and Rhinoceros. Visual artistic photographer Man

Ray and Spanish filmmaker Luis Banuel joins the table as Gil tells them that he’s

from the future travelling through time.

Gil also deals with his fear of death.

Gil also deals with his fear of death.

“Some people enter your life in a whirlwind and no

matter how hard you try you can’t stop thinking about them, even after they

leave…especially after they leave.”

– F. Scott Fitzgerald to Gil about his wife Zelda

– F. Scott Fitzgerald to Gil about his wife Zelda

Gil goes back to the Rodin female tour guide in his

present, standing by the infamous ‘Thinking Man’ and asks her about whether it’s

possible to love two women at the same time, sort of like Rodin did. Can you love them both in different ways? Gil immediately realizes that she is far more

open to the idea than he, an American, is.

Not that she is condoning it but she simply recognizes the complexity of

it as a way of life. She is right to

think this; there is a complexity to it.

Love in not exclusive, love is complex and often one sided, meaning that

one gives off love like an aerosolized fragrance, not toward something that is tactile.

Gil goes back to the Rodin female tour guide in his

present, standing by the infamous ‘Thinking Man’ and asks her about whether it’s

possible to love two women at the same time, sort of like Rodin did. Can you love them both in different ways? Gil immediately realizes that she is far more

open to the idea than he, an American, is.

Not that she is condoning it but she simply recognizes the complexity of

it as a way of life. She is right to

think this; there is a complexity to it.

Love in not exclusive, love is complex and often one sided, meaning that

one gives off love like an aerosolized fragrance, not toward something that is tactile.

“I believe that love that is true and real creates a

respite from death. All cowardice comes

from not loving, or not loving well, which is the same thing. And when the man who is brave and true looks

death squarely in the face like some rhino hunters I know, or Belmonte, who’s

truly brave. It is because they love

with sufficient passion to push death out of their minds, until it returns as

it does to all men. And then you must

make really good love again. Think about

it.”

– Ernest Hemingway

while sitting in the old car with Gil

Gil travels back to the Parisian street at midnight

and climbs into the old car and is met by Tom Eliot, Thomas Stearns Eliot,

otherwise known to the world as T.S. Eliot.

Gil is star-struck claiming that, ‘Prufrock

is his mantra.’ This is pertaining

to a poem written by T.S. Eliot called “The

Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock”, a poem structurally based heavily on the

poetic writings of Dante Alighieri and is a social poem described as ‘a drama of literary anguish’. Parts of the poem that Gil calls his mantra

are the interior dramatic monologues of a city dweller, an urban man, conveyed

by Eliot through the stream of consciousness technique. The poem’s narrator is stricken with feelings

of isolation and incapability for decisive action that is said, “to epitomize frustration and impotence of

the modern individual” and “represent

thwarted desires and modern disillusionment.”

Gil back in the 1920’s again goes to Gertrude Stein’s

and asks her thoughts on the novel he is writing. Pablo Picasso is there as well as listening

in. She tells Gil that, “we all fear death and question our place in

the universe. The artist’s job is not to

succumb to despair but find an antidote for the emptiness of existence.” The artist must create a coping mechanism of

sorts to allow the reader to figure out for themselves, what it means to be

alive for them, using these ‘antidotes’

to achieve this level of awareness. The

artist needs to sacrifice themselves for the goodwill of humanity. The artist needs to kill themselves with

their art so that many can learn from, or be shaken by the end result, thus

knocking them out of the hypnotizing nature of conformity and banality.

Gil back in the 1920’s again goes to Gertrude Stein’s

and asks her thoughts on the novel he is writing. Pablo Picasso is there as well as listening

in. She tells Gil that, “we all fear death and question our place in

the universe. The artist’s job is not to

succumb to despair but find an antidote for the emptiness of existence.” The artist must create a coping mechanism of

sorts to allow the reader to figure out for themselves, what it means to be

alive for them, using these ‘antidotes’

to achieve this level of awareness. The

artist needs to sacrifice themselves for the goodwill of humanity. The artist needs to kill themselves with

their art so that many can learn from, or be shaken by the end result, thus

knocking them out of the hypnotizing nature of conformity and banality.

Back in the present, Gil walks along the beautiful

cobblestone streets of Paris. He goes to

an antique shop and talks to a young naturally beautiful woman about the great

musical pianist Cole Porter, who wrote many stories about Paris and about how

love is part of the essence of this wonderful city. Gil buys a Cole Porter record and then

strolls along the banks of the Seine River and buys a book from the many book

havens along these river banks. The book

is written by his 1920’s love, Adriana.

He then gets a lovely Parisian woman to translate the French for him on

a park bench. Here, through the lovely voice

of this woman, Gil finds out that Adriana loved him, she writes of a dream she

has about receiving a gift from Gil. She

writes that Gil has bought her a pair of earrings and then they made passionate

love.

Naturally being a man with blood pumping through his

veins, Gil rushes home and puts together a present for Adrianna, sort of

fulfilling his perceived manifest destiny.

Gil’s fiancée Inez, notices she has earrings missing, the ones that Gil

just giftwrapped for his 1920’s love, she reports that they have been stolen by

the housekeeping staff. For a moment Inez

questions what Gil is up to but then blows the whole thing off when Gil puts

the earrings back and claims he found them.

Naturally being a man with blood pumping through his

veins, Gil rushes home and puts together a present for Adrianna, sort of

fulfilling his perceived manifest destiny.

Gil’s fiancée Inez, notices she has earrings missing, the ones that Gil

just giftwrapped for his 1920’s love, she reports that they have been stolen by

the housekeeping staff. For a moment Inez

questions what Gil is up to but then blows the whole thing off when Gil puts

the earrings back and claims he found them.

Gil goes back to 1920 and gives Gertrude Stein a revised

draft of the first few chapters of his novel to read. Henri Matisse is there selling some of his

paintings to Gertrude at the same time Gil meets up with Adriana so they can discuss

their feelings for each other. They go

for a walk on yet another majestic, beautiful, picturesque street in

Paris, with street lamps illuminating and scintillating light flickering off the

cobblestone brick street. Sitting on a

bench, Gil leans over and kisses Adriana because quite frankly, he has no

choice. Like Cole Porter sang, “You just do it, you just fall in love.” Gil gives her the earrings, Adriana, loving

them, puts them on as a stagecoach being pulled by two horses stops in front of

them. They are offered to join the coach

for some company and entertainment. Gil

and Adriana are transported to 1890’s Paris and go and sit in a dining room

hall, and then dance becoming mesmerized by their surroundings, Adriana

especially.

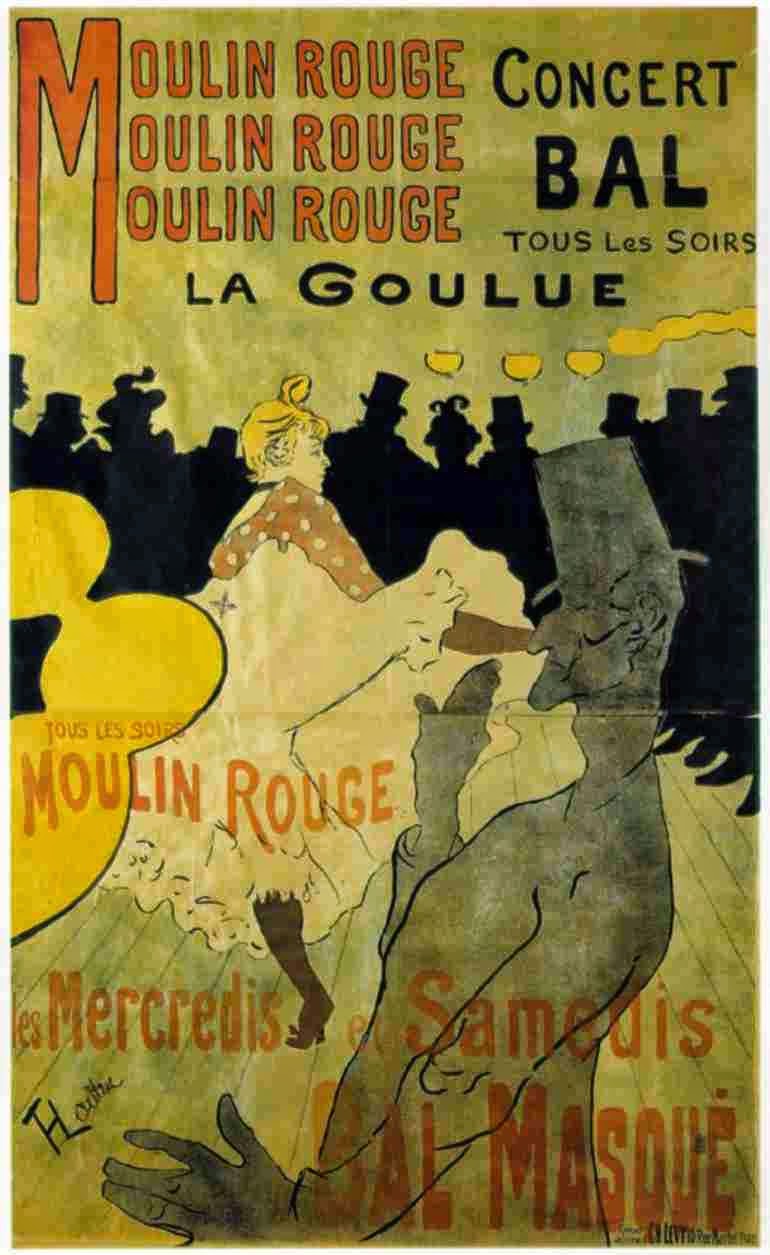

Gil and Adriana go and sit with none other than French

painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, while painters Edgar Degas and Paul Gauguin moments

later join them. Their discourse centers

on the 1890’s generation and how it is empty with no imagination or with no surprises.

Adriana laments that the 1920’s is

itself a generation with no imagination.

Here we are presented with our problem of the ‘present’ and that those

that often occupy it are discouraged about its potentiality but have no problem

praising a point in the past as being…perfect.

This scene, quite unique, displays how this particular concept, one that

Woody Allen himself would have once purported, is flawed. Gauguin thinks that the renaissance would

have been a better place to have been born into, where Adriana thinks it’s the

1890’s and Gil thinks it was the 1920’s that was the best time. Gil begins to realize that his present

calamity is that it’s filled with unimaginable people and thus he, a creative

man, is simply uninspired by his experience.

Adriana, still star struck, still mesmerized, takes

Gil aside and states that they should never go back and should stay in the 1890’s,

because she thinks the 1920’s are dull compared to where they are now. Gil tells her that the 1920’s isn’t his

present but 2010 is where he is from.

Here the realization appears that unfortunately is lost on so many in

the real world; escaping to the past is an act of futility because no matter

where you are, ‘you’ will always be there, meaning that problems are not always

solved because of relocating oneself.

Adriana, sadly, admits that she wants the illusion thus

freeing Gil of the unrealistic hold he had on his own illusion. They say their good-byes, she’s staying and

he’s going but for Gil, at this point, he wouldn’t want any other way. Gil goes to the 1920’s to Gertrude Stein’s

house to get his book, where she plants the seed that like Hemmingway, maybe

his fiancée might be cheating on him.

When Gil goes back to the present he finds out that she was in fact

cheating. Inez naturally denies having

an affair with pedantic Paul.

Adriana, sadly, admits that she wants the illusion thus

freeing Gil of the unrealistic hold he had on his own illusion. They say their good-byes, she’s staying and

he’s going but for Gil, at this point, he wouldn’t want any other way. Gil goes to the 1920’s to Gertrude Stein’s

house to get his book, where she plants the seed that like Hemmingway, maybe

his fiancée might be cheating on him.

When Gil goes back to the present he finds out that she was in fact

cheating. Inez naturally denies having

an affair with pedantic Paul.

Gil confronts his own level of cognitive dissonance as

he explains to Inez that they shouldn’t be together and should in fact be a

part. Inez admits that she did cheat on

him with Paul. Gil decides to stay in

Paris while his cheating ex-fiancée Inez and her Tea Party Republican parents

go home. Gil then meets with the girl from

the antique shop and they walk together in the rain along a bridge, enjoying

being in the present in this moment in time.

The past has always had a romantic aura about it.

The present we are responsible for, the future we can change but the past

is written, its pages are full of stories with interesting people and places

that are antiquated with big cars and cigarette smoke filled jazz clubs.

The past, not specifically our own, allows us to forget about our present

and future, it allows us to enjoy what's great about humanity guilt free.

“Maybe the present is a little unsatisfying because

life is a little unsatisfying.”

– Gil

A great moment at the end is it ends happy. Woody Allen realizes that once one sees the

reality of their existence, this doesn’t mean death. He wants his audience to know that happiness

can be found on the other side of illusion. Midnight in Paris does want us to get over ourselves as most Woody Allen films

do, but here it’s a philosopher’s journey about realizing the past without

letting it define your present.

“Nostalgia is denial – denial of the painful present…

the name for this denial is ‘golden age

thinking’, the erroneous notion that a different time period is better than

the one ones living in – it’s a flaw in the romantic imagination of those

people who find it difficult to cope with the present.”

– From Midnight in

Paris

“Peace can only

come as a natural consequence of universal enlightenment.”

No comments:

Post a Comment